Vajrayogini in Poetry

October 9, 2018 0

When you say ‘tantra’, what most people these days will probably immediately think of is not what tantra actually is. Tantra, in Buddhism at least, does not have anything to do with sex. The actual practice of tantra is about trying to control the strongest energy we have (desire) and channeling it into something that brings higher levels of awareness. It is about gathering the winds and energies as part of a specific set of instructions that deal with the most subtle areas of our mind.

Traditionally, tantra was extremely secretive. It was only when a lama surmised that their disciple was qualified, that the teacher would initiate the student into the practice. Think of it like driving a car – everyone can drive a regular car but only a few people are trained up to a point they can get into an F1 car and know how to operate it safely and successfully. To do that, you need to be dedicated to your field and have someone to train you so you know how to turn on the car, let alone get from A to B really, really fast without crashing.

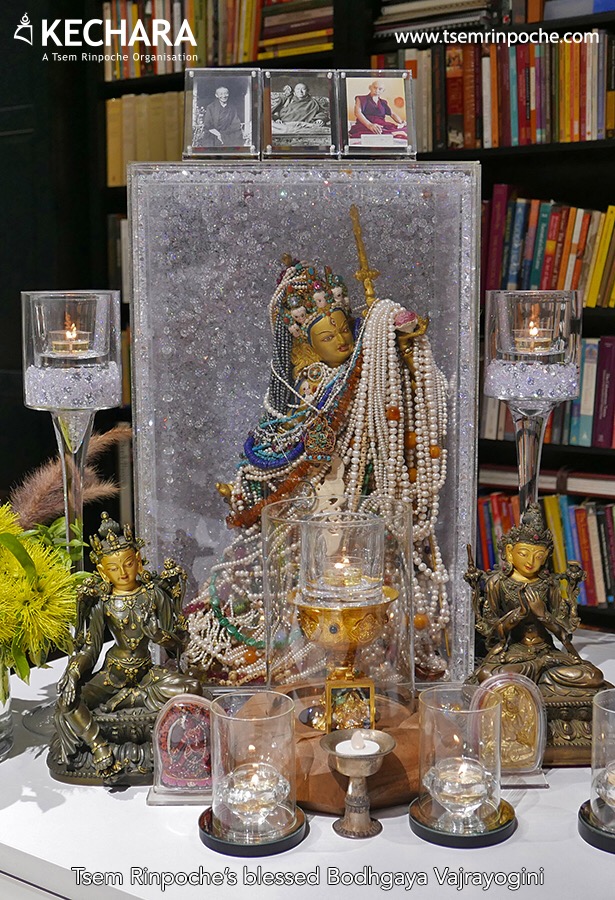

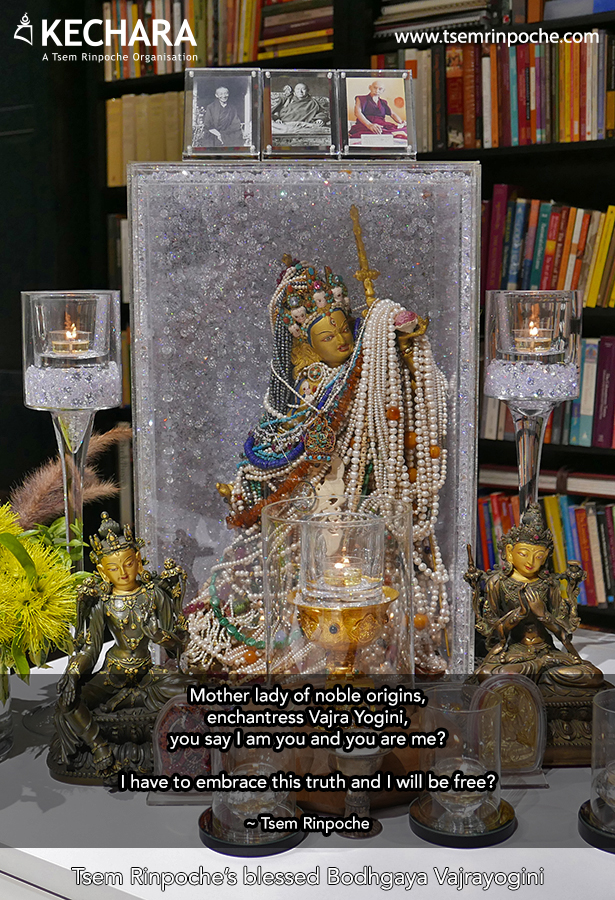

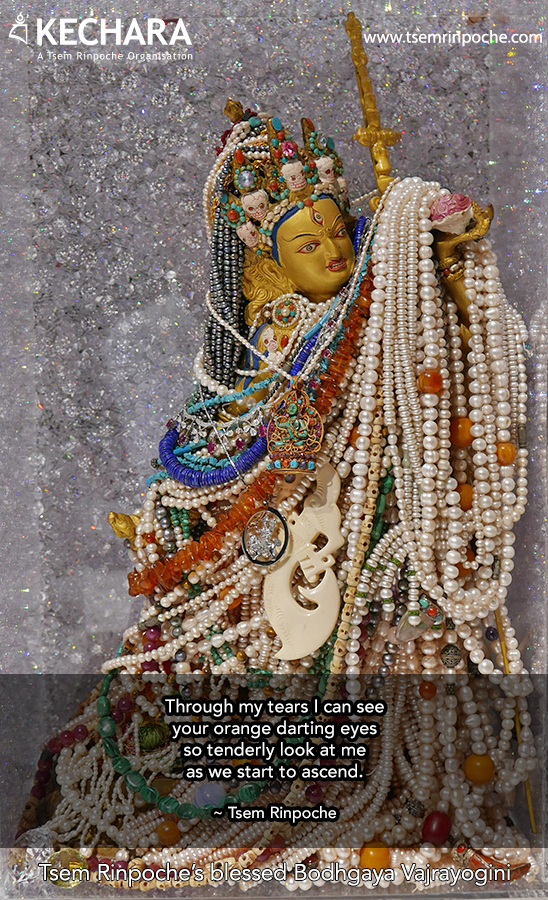

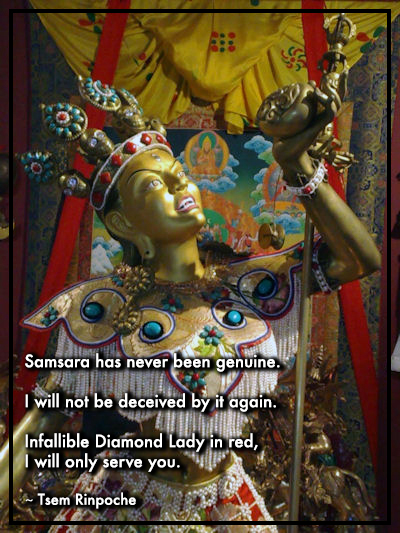

Rinpoche was offered this Vajrayogini statue by a Malaysian Buddhist under the bodhi tree in Bodhgaya, India.

These days, if you Google tantra, it is very easy to find teachings on tantra, the sadhanas (prayers), practices, visualisations and meditations but without a qualified spiritual guide, you can practise all you want and in the best case scenario, you will not gain any results from your practice (i.e. you will not know how to turn on the car). Tantra was never easily accessible in the past because in the vows taken during initiation, one of them is to refrain from revealing tantra to the unqualified. If tantra is taught to someone who is unqualified, the teacher breaks their tantric vows and for those who receive it and are not qualified, they will create the karma not to receive genuine tantra in the future. So suffice to say, many people were discouraged in this way from sharing teachings with the unqualified.

And by the way, when we talk about “unqualified” here, it does not mean those practitioners are lower or inferior or anything like that. It refers to the fact they have not made themselves qualified – returning to the analogy of the F1 car, they have not dedicated themselves to training, practice and following their driving instructor’s advice to make them qualified to drive a more powerful, complicated car.

So the poems are meant to remind the initiated of the instructions on the path and, if done well, to plant seeds of Vajrayogini in the minds of the uninitiated. Rinpoche has explained that a seed is an imprint of Enlightenment in our minds. When we see the enlightened body of Vajrayogini, we plant the body of a Buddha in our mindstream that we can achieve that body. When we hear Vajrayogini‘s name, or we hear about her tantra or her practice, then we plant the seeds of Vajrayogini‘s speech in our minds so that in the future, we will be able to achieve the Buddha’s speech. And when we hear about the qualities of Vajrayogini, it plants seeds in our minds of the enlightened mind of a Buddha.

Rinpoche’s personal altar, with his Bodhgaya Vajrayogini statue

When the seeds open, Rinpoche said that they us towards something that will help us to achieve the body, speech and mind of a Buddha. Rinpoche also explained that the seeds are important because we want to give ourselves as many chances as possible to connect with the Dharma. In our next life, perhaps we see an image of Vajrayogini or we listen to the teachings of the Panchen Lama and when that happens, something inside us is triggered and our seeds are opened, compelling us to seek our Dharma. However, the only way that seeds can be opened is if they were planted, and so that is what we are doing now.

In fact, this whole blog post arose because Rinpoche told me to write a post about the memes, so that we can plant as many seeds of Vajrayogini as possible!

Anyway, with so many people being unqualified to receive tantra, but with lamas knowing they had to compassionately plant as many seeds as possible, the tantra teachings therefore were always conveyed in hushed, mysterious and poetic tones. From this, a tradition developed of penning down the teachings in the form of poems. This would allow tantrikas familiar with the practices to automatically recognise the meaning behind the poems and any instructions it contained. Meanwhile, to the uninitiated, it would simply be a beautiful poem and a blessing for them to recite.

When it comes to tantra, Rinpoche has always been extremely strict, very careful and very, very traditional. Rinpoche trains students for years before even considering transmitting preliminary tantric practices to them. Even then, Rinpoche is highly cautious and selective about who receives it, having learned from past experiences where some students did not have the merit to support their tantric practice. So when it comes to tantric teachings, Rinpoche is very careful never to reveal too many details for those who are not initiated.

Bearing all of this in mind, it is therefore a real treat when Rinpoche does give teachings related to tantra. Recently Rinpoche gave us a short teaching on the poems below, elaborating to us some of the meanings behind them. Since we are not initiated into Vajrayogini‘s practice, Rinpoche could not go into too much detail. Nevertheless, what was shared was definitely enough to whet our appetites.

What I love about poetry, especially poetry that Rinpoche composes, is that Rinpoche not only conveys teachings but he also mirrors the state of the world and the state of our minds. How each of us interprets the poem differs based on our experience, knowledge, learning and study. So while I have done my best to recall and share here what Rinpoche conveyed to us, I am still definitely interested in your thoughts so do let me know what you think!

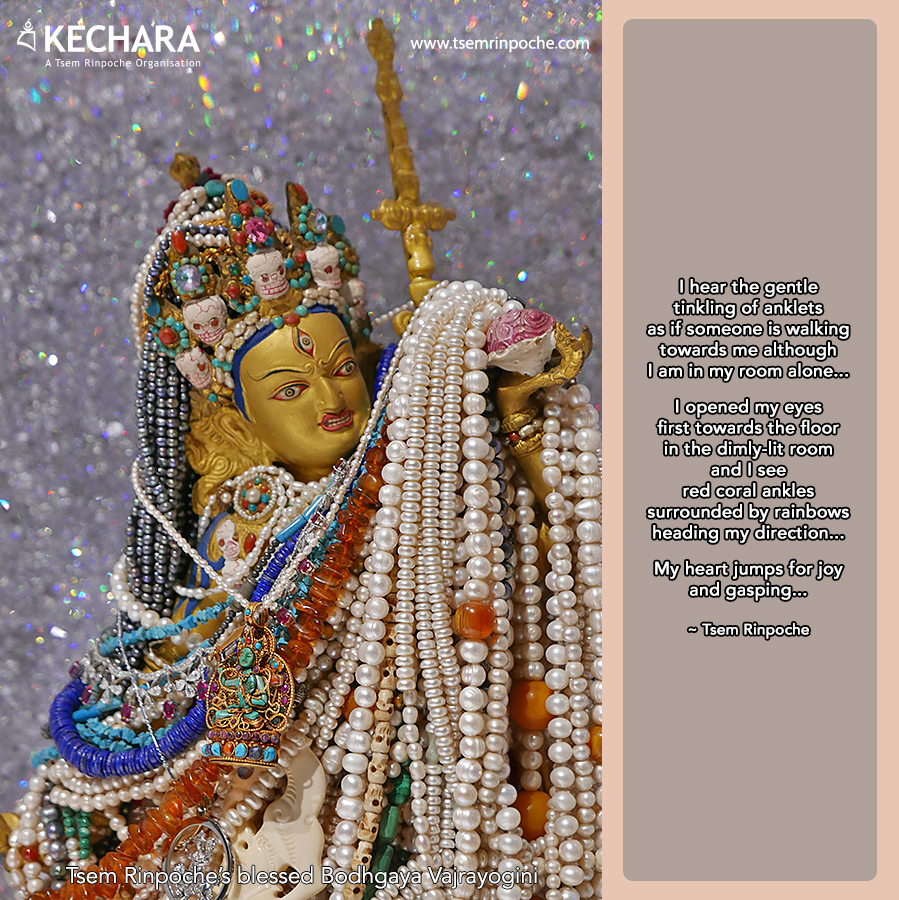

The tantras teach that when the time has come for medium capacity practitioners of Vajrayogini to ascend to her paradise, we will hear the tinkling of the small bells she wears on her ankles (just like many Indian ladies wear on their ankles).

It is said that on the day we are due to ascend to Kechara (Sanskrit; also known as Dakpo Kachö in Tibetan), red sindhura powder will spontaneously appear on the crown of our head. On that day, we should look out for a female who will appear to us with a pink bliss swirl (gakyil) on her forehead. She may appear as old, young, skinny, fat, evil, purple, white, blue, black, saintly; however she appears, when she does appear, we should immediately recite the prayer to Vajrayogini and hold on to her and not let go, no matter what happens. If we keep praying, the next feeling we will have is that of ascending; she will take us to Kechara Paradise.

‘Dimly-lit’ here refers to the clearing of our ignorance, as indicated by the darkness clearing. The poem also refers to that moment of anticipation, excitement and joy that one is about to ascend to her paradise.

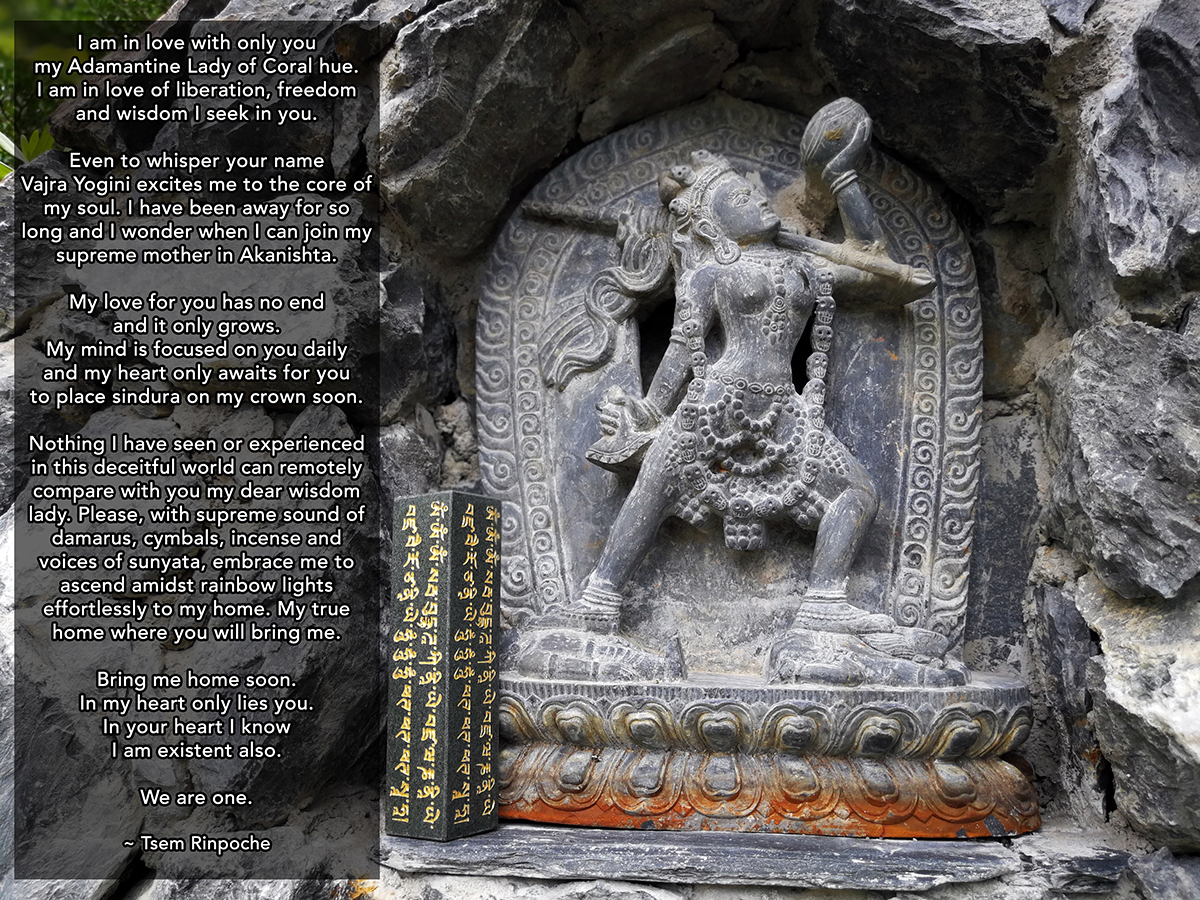

In declaring our love over and over again for Vajrayogini, it reflects our achievement of renunciation because we cannot have two mistresses at the same time. We cannot be in love with the trappings of samsara (money, power, sex, etc.), and love Vajrayogini and Enlightenment at the same time because they are diametrically opposed to one another, and there is no space for two mistresses to occupy our minds.

So when we declare we love only Vajrayogini, it is a declaration of our commitment to her practice to gain results which is liberation, freedom and wisdom; we cannot deceive her by saying we still want money and power.

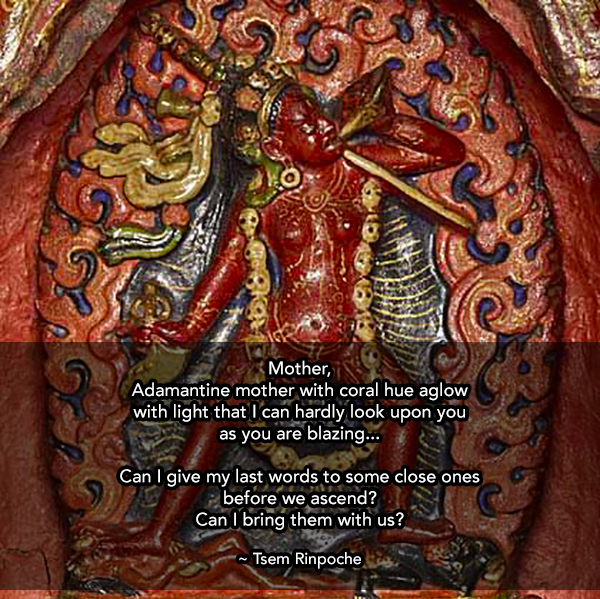

‘Adamantine’ refers to Vajrayogini‘s diamond indestructibility. The only being that is indestructible is a Buddha who has no karma to be harmed or destroyed. In calling her the ‘Adamantine Lady’ therefore, it is a declaration of Vajrayogini‘s qualities and nature as an indestructible being i.e. a Buddha.

For many people, when we talk about making money, chasing after relationships, etc., they get very excited. There is even a term for it – ‘the thrill of the chase’ or ‘the thrill of the hunt’. Hence when we declare that we are excited by Vajrayogini, it is again another declaration of our renunciation because this time, we are not excited from chasing objects that will deepen our samsara. We are chasing after Vajrayogini who will deliver us from samsara.

Rinpoche then goes on to say that we have been away for so long. It is a way of saying that we have been far removed from our Buddhanature for a very long time. We have spent aeons deepening our samsara, deepening our attachments, deepening our suffering; this part of the poem declares our recognition of that state, and how it has drawn us away from Akanishta (which is another Sanskrit term referring to Kechara Paradise, which is Vajrayogini‘s celestial abode). In reality, we have never left our Buddhanature but we have spent a long time failing to recognise it or even denying it. For me, this verse also conveys the sense of a long journey coming to an end, and the journey was towards recognising our Buddhanature and ascending to Kechara.

Then as we engage in more and deeper Dharma practice, our attachments reduce and our love for Enlightenment (as represented by Vajrayogini) grows. As it grows, and as the moment of our impending ascent to Kechara Paradise draws closer, then the red sindhura powder appears on the crown of our head.

In calling Vajrayogini ‘wisdom lady’, we are actually praising her qualities and recognising her nature. Samsara is driven by ignorance, which is the belief that if we get money, sex, power, fame, reputation, we will be happy. That is ignorant and it is the deception / deceit of samsara we fall for because it is impossible to gain stable happiness, let alone ultimate liberation, from something that is external and with impermanent value. Thus, when we call Vajrayogini ‘wisdom lady’, we are saying that she is different to everyone in samsara. She is wise above this ignorance, and therefore out of samsara i.e. a Buddha.

So when Rinpoche refers to the cymbals and drums and all that, it is speaking of the moment when we are about to ascend to Kechara. Those are the sights and sounds that we will observe around us just before we go home (Enlightenment). Home is where we were always meant to be but as a result of our actions, we have been away for a very long time. Tantra is the swift path that shows us how to get home quickly.

Rinpoche ends the poem by talking about dedication to Vajrayogini and how we are one with her. Shakyamuni taught that every one of us possesses the potential to become a Buddha. The difference between us and Vajrayogini is that we are full of unrealised potential, whereas Vajrayogini has realised her potential and become a Buddha. I also find this last line very powerful because when we ascend to Kechara Paradise, we do become one with Vajrayogini or at least we become closer to becoming one with her (one in the state of Enlightenment). Practitioners who ascend to Kechara will never fall back down again and therefore ascending to Kechara means we are one step closer to Vajrayogini and one step closer to becoming the same as her and indivisible from her (i.e. one with her).

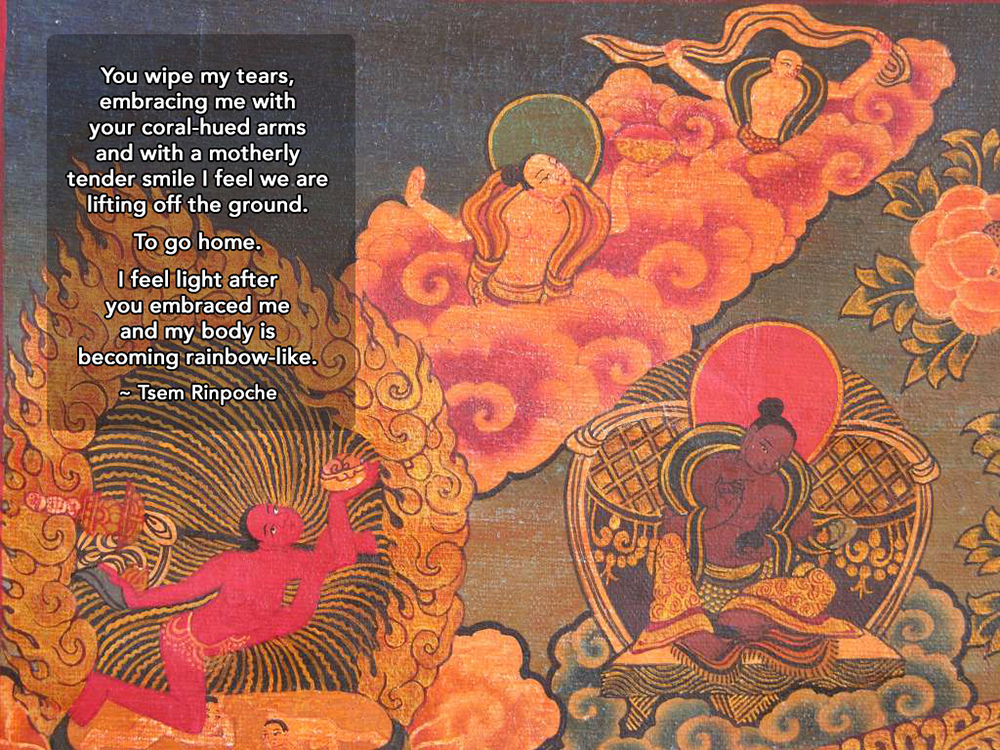

When incarcerated people are freed, they cry tears of happiness; when people leave terrible relationships, they cry tears of joy and relief. In the same way, when we finally leave the prison of samsara, we cry tears of joy because we will never suffer again and like a mother comforting her child, Vajrayogini wipes our tears away. ‘Home’ here refers to Kechara Paradise and a return to our real home, which is our Buddhanature, that we have been away from for so long.

According to the Heruka Tantras, when Mother Vajrayogini takes us to Kechara, she embraces us and kisses us like a mother kisses her child, and the four elements of our body change into that of light, like a rainbow.

For women in samsara, our secret organ is associated with increase in desire; for Vajrayogini, the Adamantine Mother, her secret organ is associated with the birth of our Enlightenment and cessation of our desire. So Rinpoche addresses Vajrayogini as ‘mother’ because she gives birth to our Buddhahood and Enlightenment. However, in this instance, she is not a normal mother; in this instance, Vajrayogini is our ‘adamantine mother’ because she is a Buddha and thus indestructible. Rinpoche always refers to her coral hue because that is what is in her sadhana.

The wisdom fire that burns around Vajrayogini is so brilliant, it is hard to look directly at her, just like how it is difficult to look directly at the sun. This brightness is one of the 112 marks of the superhuman being that is a Buddha. Here, when we talk about looking up Vajrayogini, it is reminiscent of someone having a vision of her, whereby she is so bright that it is almost unbearable to gaze upon her until our eyes adjust. For me, it is also reminiscent of sitting in the dark, which we can liken to our ignorance, and coming into the bright light of Enlightenment; that initial shock of light is almost painful until we have adjusted to it. And in the darkness, there is danger, uncertainty and a sense of helplessness and loss; in the light, there is clarity, safety and the ability to set our own direction.

Rinpoche ends the poem by making a subtle distinction between ‘close’ and ‘not close’, which is a reflection of the remnants of attachment that we still have left in our mainstreams. However, instead of just saying goodbye, we also ask Vajrayogini if we can bring them with us. It is our attainment of bodhicitta that compels us to ask Vajrayogini whether we can bring other sentient beings with us and not leave them behind.

Vajrayogini is noble because she represents the Eightfold Path to nobility. Her form, which is the embodiment of renunciation, bodhicitta and realisation of emptiness, enchants and stuns us in the same way a beautiful lady enchants men. A woman of that calibre is a rarity so when we are confronted with it, we are stunned and cannot help but stare. In the same way, someone who has achieved renunciation, bodhicitta and realisation of emptiness is also a rarity so when confronted with it, beings in samsara who are not used to such a person cannot help but stare at them.

Still, we question her because even though the tantras say that our real nature is Enlightenment, we have not realised that we are one with Vajrayogini and no different to her. But if we accept and recognise that we are one with Vajrayogini, and we embrace the truth that she represents (which is the practice of the teachings) we will be free. It also reflects the moment when Vajrayogini arrives to take you to Kechara; if you embrace her, then you will ascend to Kechara Paradise with her and you will be free.

Vajrayogini’s eyes are orange with a black iris, and they dart because she is forever looking for the suffering of others to see how she can assist. As she gazes at us tenderly, we are in tears not because we are about to ascend to Kechara but because her appearing to us means that we have finally let go of our attachments, and we are free of our selfish selves to be able to ascend to Kechara. So this poem also refers to that moment when Vajrayogini comes to hold our hand and ascend with us to Kechara.

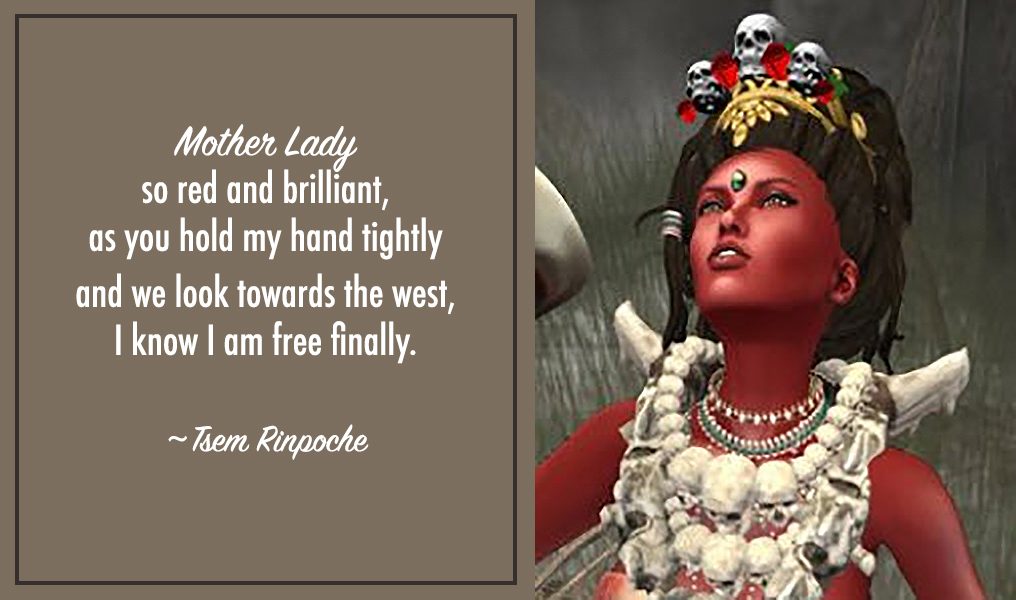

Rinpoche refers to Vajrayogini here as ‘mother’ again because she gives birth to our Enlightenment, in the same way a mother gives birth to a child. And in the same way our mothers are kind to us, Vajrayogini shows us the same kindness (and more!).

And if you notice, Rinpoche keeps talking about her being red, coral hue, ablaze in red, etc. We all know that colours have a lot of significance; green is soothing for the eyes, blue has a calming effect, white is symbolic of purity and red reflects passion and desire (Valentine’s Day, anyone?). Well in tantra, the colour red reflects the nature of her practice; that is, she has the power to attack our desire and her practice focuses on destroying that.

Now when Rinpoche refers to ‘west’ here, there is a deeper tantric meaning. First, Rinpoche talks about ‘we’ meaning both you and Vajrayogini, whose face always faces the west in the direction that she is going to take you. In any tantric practice, when you enter a deity’s mandala (their celestial abode), you as the practitioner are in the east looking west; that is what ‘west’ refers to in this poem, being that it is the location of Kechara Paradise.

For me, looking towards the west and towards Kechara can refer to two things. It can refer to the realignment of our priorities to practise whatever is necessary to enter her paradise, or it can refer to actually entering her paradise at the time of our death. All who enter Vajrayogini’s paradise, where they will receive teachings from the Mother Lady herself, will never fall back into the cyclical rebirths of samsara (hence they are free). Freedom here also refers to freedom from our attachments, from our desire, from our hatred and ignorance, and all of our hang-ups and likes and dislikes, and preferences and baggage.

The deception arises from the fact we think we will be happy if we go to school, get into a relationship, get married, have children, buy a house, buy a car, etc. But if that was what REALLY led to happiness, then how come people who have all that and more are still depressed? So in thinking we become happy by doing all that, we are deceived by samsara’s lies. Therefore nothing in samsara is genuine.

Hence when we aspire to only serve Vajrayogini, it does not mean entering servitude or becoming some kind of slave. What it means is that we will devote ourselves to the path and the Enlightenment that Vajrayogini represents, and dedicate ourselves to accomplishing that instead of accomplishing within samsara. She is someone safe for us to serve and take refuge in because she is infallible, and the only being that is infallible is a Buddha. Every one of us, no matter how intelligent, educated or experienced we are, are not infallible because there is always a chance we can make a mistake, go backwards in our practice, hurt others, etc.

This image and this poem brings me a lot of peace. In my mind, I can already hear the rustling of the wind through the trees, the gentle swaying of the branches, the shimmering of sunlight hitting the water, birds singing in joy. It is just me, nature and Manjushri and there is nothing in between us.

Recent Posts

Subscribe to Blog

Categories

Archives

Visitors by Country

| Total Pageviews: | 1 |

|---|

Leave a Reply